Anyone over a certain age will remember the Los Angeles Ant Panic of the summer of 1954. Nuclear tests in the Nevada desert over earlier years had already raised the fears of the emergence of huge mutant creatures, and when reports of gigantic ants started trickling in from Sherman Oaks and Encino, these fears seemed confirmed. When a father and his two young sons disappeared, and the father’s mutilated corpse was later discovered, the ants were blamed in the popular imagination. Mayor C. Norris Poulson, in office for less than a year and anxious to make a favorable impression upon LA citizens, called for a police taskforce which quickly went about exterminating the crawling creatures. Post-mortem examinations of the ants by entomologist Dr. Greg Bradley revealed the so-called ants to be, in fact, highly modified hermit crabs.

Birgus formicamima

Birgus? ant-mimic

It is not known what Birgus means. It may be a corruption of Burgus, meaning fort.

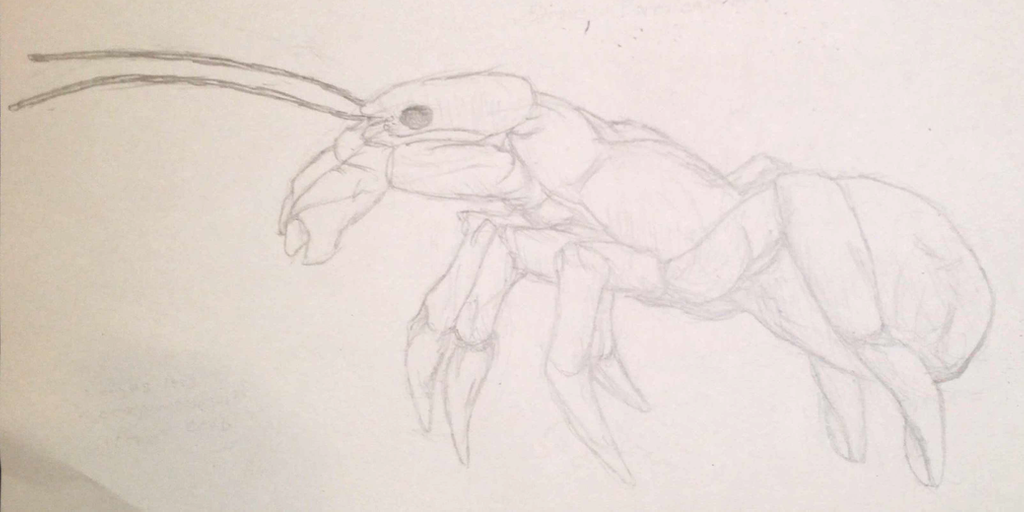

The Legionnaire Crab, also known, unfortunately, as the Sand Ant, is closely related to the coconut crab Birgus latro. Similar in body length, formicamima has a thinner cephalothorax, is overall less massive, and holds itself higher off the ground. The most obvious morphological differences between it and the coconut crab are in its legs. The front chelae are typically held against the head except when in use and are also smaller and more symmetric in size in comparison, lending to the illusion, from afar, that they are part of the head. The next two pairs of legs are also smaller in comparison with the coconut crab’s. However, the fourth pair of legs have increased in size and have had their chelae partially fuse, as these legs fulfill a much more important role in locomotion. As with coconut crabs, the final pair of legs are held inside the carapace and are only used for reproductive purposes. The changes in leg structure and body shape have allowed the legionnaire crab to move much more swiftly over uneven terrain. These differences, coupled with the overall smooth brownish hue, lend to the overall insectoid appearance of the crab. When startled or frightened, formicamima has a tendency to rear back partially onto its hind legs in order to appear larger, further maintaining the illusion of an ant-like form to nearby humans.

The legionnaire crab has also evolved several adaptions to allow its larvae to survive in fresh water. The juvenile crab, similar to other freshwater crabs, before converting fully to terrestrial life and losing the ability to breath underwater, has the ability to recover salt from its urine. However, formicamima still releases its larva freely into freshwater without allowing this stage to be passed within its eggs. Similarly, it producers many more eggs than a typical freshwater crab, lending to its propensity to appear in swarms.

The legionnaire crab also distances itself from other crabs by never utilizing a protective covering, even as a juvenile. Rather, the chitinization of the abdomen occurs early on in the crab’s life. Without needing the ability to grasp the inside of shells, the fourth pair of legs was free to develop into its current locomotive form.

The legionnaire crab is found on the western coast of the Americas from southern California to Peru and in the Caribbean. It is assumed that the crabs crossed into the Atlantic through somewhere in Central America, likely Panama, as they are not able to withstand the polar temperatures required for solely oceanic travel. Small population are found in Brazil and on various islands extending to the Line Islands. Though it is able to freely move on land, it must find bodies of water, fresh or saline, in order to breed.

With a very strong sense of smell, the crab is able to quickly search out food on land. Being omnivorous, the crabs will eat anything ranging from fruit to small animals, such as rats. However, they pose no danger to humans. While it is true that the deceased LA father showed signs of feeding by the crabs, all such feeding occurred well after his death. Unfortunately, his death and the presumed deaths of his two sons have never been solved.

The LA case poses another mystery for investigators. Where exactly did the legionnaire crabs come from, and how did they appear so suddenly? Dr. Harold Medford, the namer of the species, suggested that they either matured from juveniles who crawled up the Los Angeles River or larva which matured in Sepulveda Basin. This has been generally accepted, especially due to the location of the initial sightings. However, this still begs the question why the crabs appeared all at once. Though it grows faster than the coconut crab, the legionnaire crab still requires many successive moltings to grow to a large size, and these were mature individuals. Why had no younger crabs been reported before? Had the reports or the crabs themselves been ignored?

The LA incident wasn’t the only time that the crabs had poor interactions with humans. Residents of North Bimini Island in the Bahamas had embraced their own colony of legionnaire crabs, allowing them to roam the roads and often setting out food for them. However, Floridian land developer Marilyn Fryser became convinced that the “ants” were using pheromones to control the islanders and rallied a group of tourists to fight them. This, unfortunately, resulted in much of Bailey Town burning down. Many of the tourists were jailed, but Fryser managed to escape punishment. Some claim that this was an intentional charade by Fryser in order to purchase the beachfront property on Bimini for a much lower cost, but this have never been proven.

br>Certainly, legionnaire crabs loom large in the popular imagination, not just limited to the early reports of their size. Towns in the American Southwest ranging from Lizard Breath, Nevada to Alamogordo, New Mexico commonly report sightings of these creatures, despite the fact that in many of these cases there lack insufficient sources of water nearby in which the crabs could breed. Cryptozoologists still set out to scour the landscapes for the underground caverns and aquifers the crabs supposedly inhabit, but are often too embarrassed to ever show their faces in town again.

In 1977, the discovery of a similar species of crab, more closely related to formicamima than latro, turned some theories on its evolution onto their heads. Previously, it was assumed that formicamima’s unusual leg structure and gate evolved after its larvae took to freshwater, allowing it to travel and survive better in an inland environment. However, the new species, Birgus marina, has a similar morphology while living only on islands in the Pacific Ocean; the larvae merely will float in the ocean’s pelagic zone. It seems that evolutionary factors even on islands may favor the increased locomotion present in marina and formicamima. As in most cases the island crabs are faced with little predation, perhaps the adaption is driven by competition for scarce food sources.

Birgus marina was once endemic to islands ranging from Palmyra Atoll to Rapa Nui, however, it is currently considered critically endangered. The causes of its decline are not entirely understood, and may not be consistent from location to location, but it is known to have been driven to localized extinction on Rapa Nui by hunting prior to the arrival of Europeans. The Polynesian rat has also been implicated as a contributing factor to its endangerment.

The naming of these two species is currently controversial. In the paper which named marina, the authors suggested that it and formicamima might be grouped under a different genus separate from Birgus. Dr. Harold Medford, very vocal in his belief that most genera are two narrow, sarcastically named this new genus Haec in a recent paper. Haec literally means ‘this’ in Latin. However, somewhat serendipitously, it shares its form with the neuter plural form of the same word, which can be used as a pronoun meaning ‘them’ as well as an adjective, the same term the an early child witness of the LA legionnaire crabs famously used to refer to them. Currently, the scientific community has no consensus on which of these genus names are proper. I prefer the use of Haec as the genus for the two species, but, due to the popular familiarity with the older scientific name, I have used it in this text.

While the species was first named following the Los Angeles incident, this may not be the first time the crab was described in literature. Charles Darwin described a species “with closely allied habits” to Burgus [sic] latro, that was “said to inhabit a single coral island north of the Society group [traditionally assumed to refer to Teraina, also known as Washington Island]” (qtd. on pg. 72; Streets, 1877). This would describe the westernmost range of formicamima. However, it has also been interpreted as referring to marina, as these crabs were historically found in greater numbers in the Line Islands.

The next possible historical reference occurs in the 1906 issue of the British Journal of Entomology and Natural History. Based on the experiences of a Lancashire engineer referred to only by the pseudonym of Holroyd, which he previously related in a self-published article in The Strand Magazine, the author extrapolated the existence of large ant-like invertebrates in the upper Amazon basin. Based on Holroyd’s account and an anatomical drawing of a severed arthropodal leg made by botanist José Celestino Mutis, the author supposed that Holroyd might have seen a colony of large crustaceans related to crabs. Modern surveys have found a colony of legionnaire crabs in the lower Amazon, so it is conceivable. However, much of Holroyd’s narrative is fanciful and his story is likely a hoax.

The legionnaire crab has also evolved several adaptions to allow its larvae to survive in fresh water. The juvenile crab, similar to other freshwater crabs, before converting fully to terrestrial life and losing the ability to breath underwater, has the ability to recover salt from its urine. However, formicamima still releases its larva freely into freshwater without allowing this stage to be passed within its eggs. Similarly, it producers many more eggs than a typical freshwater crab, lending to its propensity to appear in swarms.

The legionnaire crab also distances itself from other crabs by never utilizing a protective covering, even as a juvenile. Rather, the chitinization of the abdomen occurs early on in the crab’s life. Without needing the ability to grasp the inside of shells, the fourth pair of legs was free to develop into its current locomotive form.

The legionnaire crab is found on the western coast of the Americas from southern California to Peru and in the Caribbean. It is assumed that the crabs crossed into the Atlantic through somewhere in Central America, likely Panama, as they are not able to withstand the polar temperatures required for solely oceanic travel. Small population are found in Brazil and on various islands extending to the Line Islands. Though it is able to freely move on land, it must find bodies of water, fresh or saline, in order to breed.

With a very strong sense of smell, the crab is able to quickly search out food on land. Being omnivorous, the crabs will eat anything ranging from fruit to small animals, such as rats. However, they pose no danger to humans. While it is true that the deceased LA father showed signs of feeding by the crabs, all such feeding occurred well after his death. Unfortunately, his death and the presumed deaths of his two sons have never been solved.

The LA case poses another mystery for investigators. Where exactly did the legionnaire crabs come from, and how did they appear so suddenly? Dr. Harold Medford, the namer of the species, suggested that they either matured from juveniles who crawled up the Los Angeles River or larva which matured in Sepulveda Basin. This has been generally accepted, especially due to the location of the initial sightings. However, this still begs the question why the crabs appeared all at once. Though it grows faster than the coconut crab, the legionnaire crab still requires many successive moltings to grow to a large size, and these were mature individuals. Why had no younger crabs been reported before? Had the reports or the crabs themselves been ignored?

The LA incident wasn’t the only time that the crabs had poor interactions with humans. Residents of North Bimini Island in the Bahamas had embraced their own colony of legionnaire crabs, allowing them to roam the roads and often setting out food for them. However, Floridian land developer Marilyn Fryser became convinced that the “ants” were using pheromones to control the islanders and rallied a group of tourists to fight them. This, unfortunately, resulted in much of Bailey Town burning down. Many of the tourists were jailed, but Fryser managed to escape punishment. Some claim that this was an intentional charade by Fryser in order to purchase the beachfront property on Bimini for a much lower cost, but this have never been proven.

br>Certainly, legionnaire crabs loom large in the popular imagination, not just limited to the early reports of their size. Towns in the American Southwest ranging from Lizard Breath, Nevada to Alamogordo, New Mexico commonly report sightings of these creatures, despite the fact that in many of these cases there lack insufficient sources of water nearby in which the crabs could breed. Cryptozoologists still set out to scour the landscapes for the underground caverns and aquifers the crabs supposedly inhabit, but are often too embarrassed to ever show their faces in town again.

In 1977, the discovery of a similar species of crab, more closely related to formicamima than latro, turned some theories on its evolution onto their heads. Previously, it was assumed that formicamima’s unusual leg structure and gate evolved after its larvae took to freshwater, allowing it to travel and survive better in an inland environment. However, the new species, Birgus marina, has a similar morphology while living only on islands in the Pacific Ocean; the larvae merely will float in the ocean’s pelagic zone. It seems that evolutionary factors even on islands may favor the increased locomotion present in marina and formicamima. As in most cases the island crabs are faced with little predation, perhaps the adaption is driven by competition for scarce food sources.

Birgus marina was once endemic to islands ranging from Palmyra Atoll to Rapa Nui, however, it is currently considered critically endangered. The causes of its decline are not entirely understood, and may not be consistent from location to location, but it is known to have been driven to localized extinction on Rapa Nui by hunting prior to the arrival of Europeans. The Polynesian rat has also been implicated as a contributing factor to its endangerment.

The naming of these two species is currently controversial. In the paper which named marina, the authors suggested that it and formicamima might be grouped under a different genus separate from Birgus. Dr. Harold Medford, very vocal in his belief that most genera are two narrow, sarcastically named this new genus Haec in a recent paper. Haec literally means ‘this’ in Latin. However, somewhat serendipitously, it shares its form with the neuter plural form of the same word, which can be used as a pronoun meaning ‘them’ as well as an adjective, the same term the an early child witness of the LA legionnaire crabs famously used to refer to them. Currently, the scientific community has no consensus on which of these genus names are proper. I prefer the use of Haec as the genus for the two species, but, due to the popular familiarity with the older scientific name, I have used it in this text.

While the species was first named following the Los Angeles incident, this may not be the first time the crab was described in literature. Charles Darwin described a species “with closely allied habits” to Burgus [sic] latro, that was “said to inhabit a single coral island north of the Society group [traditionally assumed to refer to Teraina, also known as Washington Island]” (qtd. on pg. 72; Streets, 1877). This would describe the westernmost range of formicamima. However, it has also been interpreted as referring to marina, as these crabs were historically found in greater numbers in the Line Islands.

The next possible historical reference occurs in the 1906 issue of the British Journal of Entomology and Natural History. Based on the experiences of a Lancashire engineer referred to only by the pseudonym of Holroyd, which he previously related in a self-published article in The Strand Magazine, the author extrapolated the existence of large ant-like invertebrates in the upper Amazon basin. Based on Holroyd’s account and an anatomical drawing of a severed arthropodal leg made by botanist José Celestino Mutis, the author supposed that Holroyd might have seen a colony of large crustaceans related to crabs. Modern surveys have found a colony of legionnaire crabs in the lower Amazon, so it is conceivable. However, much of Holroyd’s narrative is fanciful and his story is likely a hoax.

Thomas H. Streets (1877). "Some account of the natural history of the Fanning group of islands". The American Naturalist 11 (2): 65–72. doi:10.1086/271824. JSTOR 2448050.