The islands bridging Southeast Asia and Australia have facilitated the evolution of several different lineages of marine carnivorous reptiles: the saltwater crocodile swims throughout Indonesia, the sea snaked of Hydrophiinae originate in Melanesia, Dumeril’s monitor will dive for crabs, even the Komodo dragon has been known to swim from island to island. It should come as no surprise that another such group has its origins here, the rhedosaurs.

Named after reporter John Rhedon, rhedosaurs are large, carnivorous oceanic lizards. They have evolved convergently many similarities with Mesozoic mosasaurs, though the two groups took to the seas separately. Rhedosaurs have evolved to be heterothermic, maintaining a warm body temperature during periods of activity, but declining into regional endothermy in the head and abdomen during periods of half sleep in which the Rhedosaur is unmoving and only partially conscious of its surroundings. Rhedosaurs are surprisingly vocal for a non-avian reptile, typically producing deep bellowing vocalizations somewhat similar to that of whales. They also seem to occasionally engage in a primitive form of echolocation, nowhere near as advanced of that of cetaceans. Rhedosaurs have an ability to remain underwater for lengths much more comparable to a seal than a dolphin, and thus tend to swim several meters under the surface of the water when traveling, only surfacing to breath. However, when male rhedosaurs are in season, they sometimes swim so that the enlarged scutes that line their back are exposed, even when females are not present. Female rhedosaurs will use the height and shape of these projections above the water level to judge the quality of potential mates. It is when male rhedosaurs are in season that they can be the most dangerous for humans, as they tend to swim closer to coastline and will attack other animals and objects in the water in “competition” for mates. After breeding, female rhedosaurs also retain their eggs, giving live birth while floating at the surface of the ocean in calm water.

Currently rhedosaurs only inhabit the Northern Pacific Ocean and along the Pacific Rim, through prehistoric rhedosaurs could also be found in the Indian Ocean. There are scattered reports of rhedosaurs from the Atlantic, but none can be confirmed. The oceanic cryptid known commonly as Gorgo, said to inhabit the Hudson Canyon but with sightings as far away as Britain and the Azores, is sometimes argued to be a rhedosaur. However, it is likely that cold currents allow the southern tips of Africa and South America prevent the rhedosaurs from entering the Atlantic, as cold temperatures are harder for the rhedosaurs to weather in torpor.

Basal Rhedosaurids were small to midsized semiaquatic carnivorous lizards fond throughout China and Southeast Asia during the Cretaceous and Paleogene. They share many features with varanids, but analysis traditionally places the Chinese crocodile lizard as their closest living relative. One disguiguishing feature of these Rhedosaurids is that their forelimbs were longer and held more upright in relation to their hindlimbs. True Rhedosaurines first appeared approximately 20 mya in what would become Indonesia, though the early fossil record is scant.

Four genera contain the five living species of rhedosaur.

Rhedosaurs (Rhedon's Lizards)

Note the misspelling in the subheading, characteristic of sub-par journalism.

Kawakolus hashirui

The smallest extant rhedosaur, the hashirui, whose name likely derives from a portmanteau of the Japanese words for seal, shiru, and reptile, hachurui, is often overlooked. Only about 12 feet long as an adult, hashirui can and will haul themselves onto land. However, they are unable to move quickly and tend to not come ashore if threats of predators exist. In areas with higher numbers of people, they have become acclimated with people and will behave relatively fearlessly.

Note that for much of history, the hashirui was considered semi-cyrptozoological by western scientists, and did not receive a proper scientific name until the mid-fifties, following a wave of interest in rhedosaurs.

The hashirui is most well-known for its role in Ishiro Honda’s documentary Gojira, detailing the rebuilding of Nagasaki in the decades following the bomb. It is this association with the city that led to its second common name, the Nagasaki rhedosaur

Note that for much of history, the hashirui was considered semi-cyrptozoological by western scientists, and did not receive a proper scientific name until the mid-fifties, following a wave of interest in rhedosaurs.

The hashirui is most well-known for its role in Ishiro Honda’s documentary Gojira, detailing the rebuilding of Nagasaki in the decades following the bomb. It is this association with the city that led to its second common name, the Nagasaki rhedosaur

Kawakolus ryujin

Named after a dragon god of the sea from Shinto mythology, the Japanese rhedosaur can be found throughout the Sea of Japan, Yellow Sea, and East China Sea as well as nearby regions of the Pacific. Somewhat larger than the hashirui, it is fully oceanic. Along with the usual rhedosaur diet of fish, it also consumes is the only rhedosaur to consume jellyfish. Surprisingly, the ryujin’s population has actually increased along with the fishing of dolphins, as the ryujin, noted for having particularly noxious flesh, faces less and less competition.

Rhedosaurus luciquaer

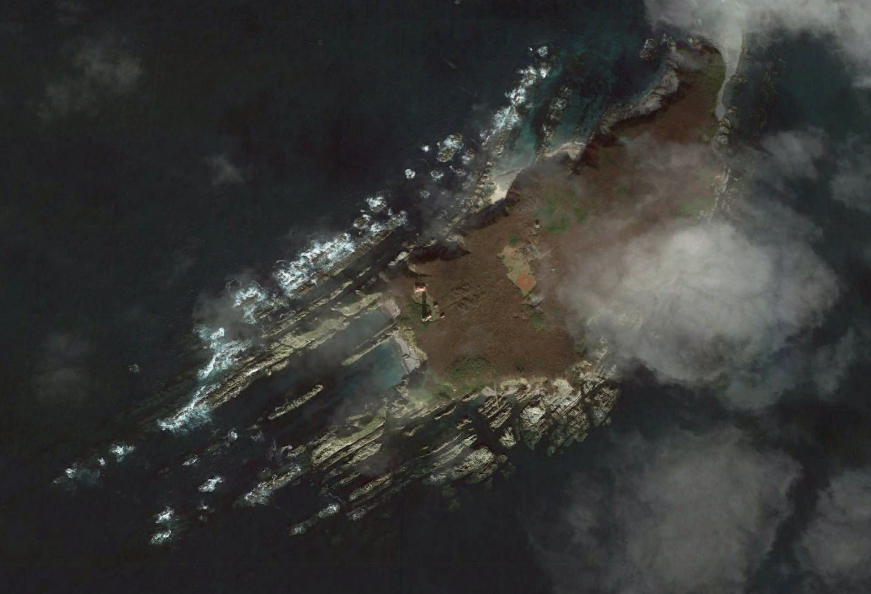

The first truly giant rhedosaur to be officially discovered and named, the shortfaced rhedosaur was described in 1953 by biologist Thurgood Elson, following a beaching of a mature individual on Destruction Island off the Washington coast.

The individual, measuring at over 45 feet long, initially appeared dead. The Coast Guard employees stationed at the lighthouse radioed out about the creature, eventually leading to a junior reporter, John Rhedon, and cameraman from The Olympian arriving at the island. However, when approached by a Coast Guard employee managing the lighthouse, it returned to life and bit at the man, causing his right leg to be severely mangled; it would later be amputated at the hospital. Those present did not approach the rhedosaur after this, but the rhedosaur soon expired from exhaustion. Rhedon quickly sent a telegram back to the paper detailing the basic facts of the incident; it was at this point that the famous misunderstanding occurred. Rhedon wrote the line “NEAR DESTRUCTION ISLAND LIGHT STOP” intending it a reference to the specific location of the carcass, however, the editor interpreted it as referring to the near destruction of the lighthouse, presumably as a result of the beast. Thus, for two days news sources reported that the rhedosaur, often misidentified as a dinosaur, had been both much more locomotive and destructive than in actuality.

Today, the habits of the shortfaced rhedosaur are much better understood. An oceanic top predator, it will feed on seals, fish, and porpoises. Its range is traditionally associated with the western coast of North America.

The individual, measuring at over 45 feet long, initially appeared dead. The Coast Guard employees stationed at the lighthouse radioed out about the creature, eventually leading to a junior reporter, John Rhedon, and cameraman from The Olympian arriving at the island. However, when approached by a Coast Guard employee managing the lighthouse, it returned to life and bit at the man, causing his right leg to be severely mangled; it would later be amputated at the hospital. Those present did not approach the rhedosaur after this, but the rhedosaur soon expired from exhaustion. Rhedon quickly sent a telegram back to the paper detailing the basic facts of the incident; it was at this point that the famous misunderstanding occurred. Rhedon wrote the line “NEAR DESTRUCTION ISLAND LIGHT STOP” intending it a reference to the specific location of the carcass, however, the editor interpreted it as referring to the near destruction of the lighthouse, presumably as a result of the beast. Thus, for two days news sources reported that the rhedosaur, often misidentified as a dinosaur, had been both much more locomotive and destructive than in actuality.

Today, the habits of the shortfaced rhedosaur are much better understood. An oceanic top predator, it will feed on seals, fish, and porpoises. Its range is traditionally associated with the western coast of North America.

Destruction Island, the Isla de Dolores, a part of the Quillayute Needles National Wildlife Refuge.

It is thought that the rhedosaur, attracted or repulsed by something, remained in the shallow waters of the cove until high tide left it stranded on land. Unfortunately, a combination of dehydration and exhaustion killed in before low tide could allow it to free itself. Enlisting the help of others present, Rhedon managed to save the carcass for study and prevent it from floating off at sea. Since then, several instances of beached luciquaer have been associated with lighthouses. There are several conflicting theories on why this may occur. An early theory supposed that shortfaced rhedosaurs mistake the sound of a foghorn for other rhedosaurs. While further research needs to be done, the sounds are not particularly similar in tone or volume. It has also been suggested that the rhedosaur may confuse the light with the bioluminescence of a prey organism. A few, particularly dim, non-scientist authors, have suggested that rhedosaurs really on astral navigation and are confusing the light with the moon, despite the fact that the moon doesn’t blink. Herpetologist Lee Hunter criticizes the proceeding explanations for portraying the rhedosaurs as dumb brutes, and instead suggested that they perhaps recognize that lighthouses signify the sort of rocky coast they will frequent for certain types of hunting and that a small percentage of the rhedosaurs present end up accidently beaching themselves. He admits that even though this is likely not the case, there is also a good chance that such a perceived correlation is merely a coincidence.

Hydrarchos rediremosam

The only surviving member of the Indian lineage of Rhedosaurs, morphologically it appears similar to Cretaceous mosasaurs with a lengthened snout and more derived flippers. Its elongated body and tail give it a much more serpentine appearance than traditional rhedosaurs. Currently it only inhabits Indonesian waters and is considered critically endangered, but members of the Hydrarchos genus were once common along the coasts of Southern Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Africa.

Abyssos kalamariphilos

The squid-eating, or abyssal, rhedosaur is found on both sides of the Pacific. As obvious from its name, it is a specialized consumer of squid, though it is no way restricted from consuming fish. Abyssos was first thought to feed solely in a manner reminiscent of the sperm whale. While the rhedosaur will dive rather deeply, it is hampered by the lack of developed echolocation abilities. Instead, it often feeds from schools of pelagic or coastal squid such as the opalescent inshore squid.

Read More: Gojira: In the Shadow of Glory